Recall: how do we help our pupils remember?

At some point in every teacher’s career you will have no doubt asked yourself, “Why can’t my class remember this? I only taught it last term/this week/one hour ago!”. In this post, Vanessa Sullivan explores seminal research on recall and its links to fluency, spaced repetition and classroom practice.

For many years, cognitive psychology has held the explanation and potential solutions. However it is only in recent years, this scientific research has found itself more readily being shared with teachers in the classroom to improve outcomes. Indeed, in OFSTED’s most recent Education Inspection Framework it states, “It is, therefore, important that we use approaches that help pupils to integrate new knowledge into the long-term memory and make enduring connections….”

The more confident of pupils will question your teaching methodology by asking, “Why are we doing this?” but actually they are entitled to understand our chosen pedagogy, as we ask ourselves the same questions. It is for this reason, I set about teaching my year 5 and 6 class about the Forgetting Curve. Whilst the methodology of the original Ebbinghaus experiment would perhaps not be considered sufficiently rigorous today, the key principles have been experimentally replicated since.

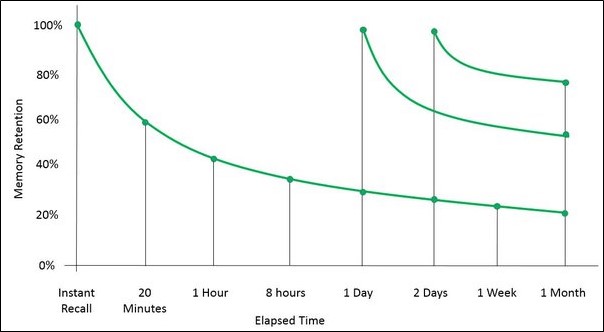

In the visual presentation below, it is very clear to see the relationship between the amount of time passed and how quickly newly taught information is forgotten, if not practised and revisited, compared to how much better recall is, when it is revised at key intervals (here, a day, 2 days, a week and a month):

We are all working towards the magical goal of “fluency” in particular skills at any age group: times table recall, vocabulary definitions, sight word recognition in reading, etc. Fluency forms the foundation, on which we build higher level skills and deeper conceptual understanding, and so it is of critical importance: we need to help children combat the forgetting curve. Spaced repetition to promote active recall is an effective technique (as borne out by a large evidence base); this is one such example in my own practice. In our Foundation subject teaching, we start each topic by looking at the core and spend some time creating definitions and then refer to it at various points during that lesson. In every subsequent weekly lesson in that unit, we then test our memory for the definitions and then finally in an end of topic assessment task. In future units of work, this same vocabulary is then revisited through games, quizzing and questioning. This is beginning to yield observable longer term results.

There are many teaching strategies which can be used in everyday practice, such as the use of Retrieval Grids, memory dumps and low stakes testing, which I will explore in subsequent posts but in the meantime perhaps consider this: how much future teaching time will you save yourself, if your pupils can retain what they are taught now?

Want to know more?

https://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/an-annotated-forgetting-curve/

Written by Vanessa Sullivan, St Peter’s CE V/C Primary School, Coggeshall

Read our other blog posts here.